As of 2023, May has officially been designated as Washington Volcano Preparedness Month. Read the official proclamation here.

For many, “ring of fire” refers to a 1963 Johnny Cash hit. The term means something very different here in Washington state: volcanoes.

We climb them, we hike around them, we live near them, and we stare up at them in awestruck wonder. For many Washingtonians, these slumbering giants seem harmless, but it’s important to learn about the risks they pose and how to prepare for the devastation they can cause.

Volcanoes in WA

Washington is situated within the Ring of Fire, a horseshoe shaped band of volcanic activity which stretches up from New Zealand to Alaska and back down to Chile.1 The formation of the Ring of Fire is attributed to plate tectonics, creating subduction zones where magma is able to rise through the Earth’s crust towards the surface.

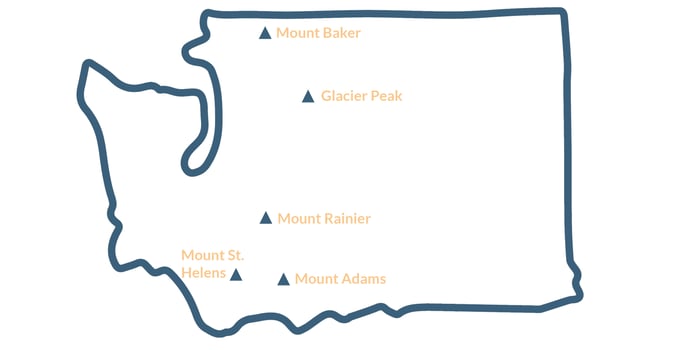

There are 452 volcanoes scattered around the Pacific Ocean; Washington is home to five. The Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and USGS have identified five active stratovolcanoes: Mount Baker (Kulshan), Glacier Peak (Takobia), Mount Adams (Klickitat), Mount Rainier (Tahoma), and Mount St. Helens (Louwala-Clough).2

All five volcanos in Washington are stratovolcanoes, a specific type of volcano with a steep, conical formation comprised of hardened lava and pyroclastic rock.3

Within the contiguous United States, Washington and California are the only states to have experienced volcanic eruptions in the last 150 years. In fact, all five Washington volcanoes, apart from Mount Adams, have erupted at least once in the last 250 years. Volcanic eruptions in the region may be rare, but they certainly aren’t an impossibility; residents of Washington must educate themselves on the dangers.

Volcanic hazards

Exploring the volcanic processes which are likely to occur in the event of an eruption gives us an idea of the danger this mountain poses.

Near Volcano Processes

For most of the other stratovolcanoes in Washington, near volcano processes are not expected to create an impact beyond the immediate slopes of the volcano, so people and property at a greater distance are unlikely to be directly affected. However, as these mountains continue to be popular destinations for year-round outdoor activities, loss of life and property in the event of an eruption are likely.

Lava flows

Molten rock that can flow out of volcanic vents and travel downhill.

Pyroclastic flows

Fast-moving mixtures of hot gas, ash, and volcanic rock which can travel at speeds of up to 450 miles per hour and reach temperatures of over 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit. Pyroclastic flows can cause widespread destruction, burying everything in their path under layers of ash and debris.4

Rockfalls

Detached chunks of solid rock which tumble downhill after becoming detached. Rockfalls can be triggered by a variety of factors, including explosive eruptions, seismic activity, and weathering of the volcanic rock.5

Ballistic ejecta

Fragments of volcanic material, such as rocks, ash, and pumice, thrust airborne during explosive volcanic eruptions.

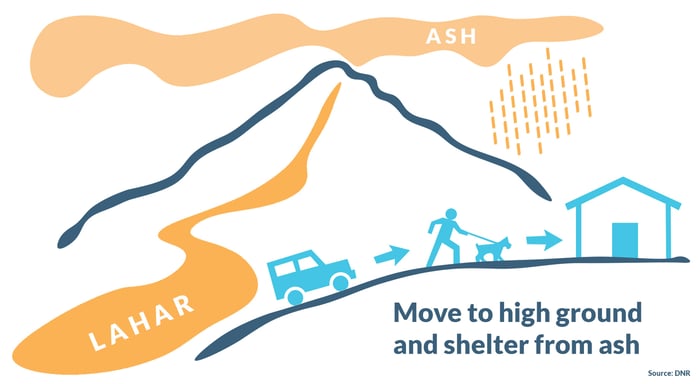

Lahars

Mudflows which occur during or after volcanic eruptions. Composed of volcanic ash, debris, and water, lahars are a slippery slurry of material that flows downhill. Lahars normally follow the path of least resistance, namely the river valleys and drainage channels that lead away from the volcano.6

Lahars are a prominent hazard for Mount Rainier and communities near its base, especially due to the large population located nearby.7 Mount Baker and Glacier peak are similarly situated in proximity to larger population centers; Mount Adams and Mount St. Helens are more remote.

Volcanic Ash

Fine grains of glass, minerals, and rock that is ejected into the air during volcanic eruptions. Volcanic ash can be carried by the wind for thousands of miles, causing significant danger to human health.

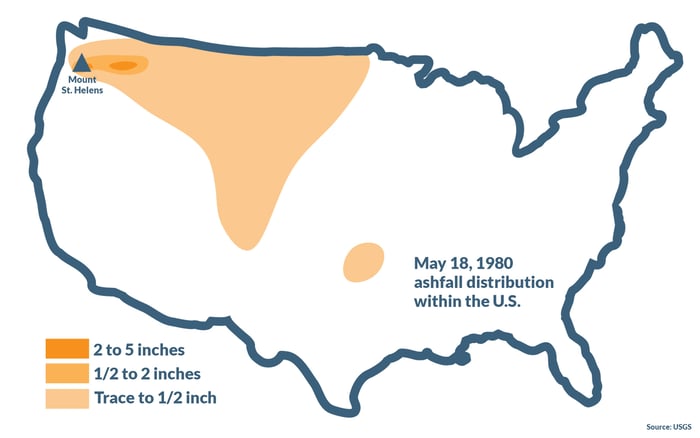

As evidenced by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, an eruption has the potential to spread ash across vast distances, not only the immediate area. The eruption of St. Helens distributed ash across the western states, reaching as far as Oklahoma.

Related:

Mount St. Helens: A History

To get a better understanding of what volcano-related risk looks like, check out this hazard map of Mount Rainier.8

Access additional hazard maps for volcanos in Washington state here:

Preparation and evacuation

Education is the most important tool individuals can have to protect themselves and their family in the event of a volcanic eruption.9 Included in this section are actions you can take to prepare.

Before an eruption

- Familiarize yourself with potential risks, especially those that could affect you at home, work, and during your leisure activities/travels.

- Store emergency supplies, food, and water in case of an emergency, including goggles and disposable breathing masks to protect against ash and dust. For further emergency preparation guidance, please reference the Emergency Preparedness Guide, compiled by Washington State Emergency Management.

- Create a family emergency plan, including communication strategies and an evacuation plan.

- Check with local and state emergency offices and schools for their response plans, and be ready to comply with official guidance.

- Sign up for the Volcano Notification Service (VNS) to receive alerts about specific volcanoes

During an eruption

- Listen to evacuation orders and leave the area immediately.

- Avoid river valleys and other low-lying areas that are at risk of lahars.

- If you notice an approaching lahar, head to high ground and find shelter. Follow evacuation route signs if available.

- Keep an eye out for updates and instructions.

- Listen for All Hazard Alert Broadcast sirens that warn of lahars.

- If you are able to, help others, including your neighbors.

After an eruption

- Do not approach the eruption site.

- Stay indoors and avoid downwind areas.

- Be mindful of lahars and landslides, which may occur long after the initial eruption.

- Head to a designated public shelter or evacuation area. Text your ZIP code to 43362 (4FEMA) with the message SHELTER to locate the nearest shelter.

- Keep an eye out for additional instructions and information. Tune in to NOAA Weather Radio, TV, radio, or online sources for official updates.

In the event of ashfall10

The number one thing to focus on is protecting your lungs. Ash, a fine blend of microscopic glass and other particulate matter, can cause severe damage to lungs or even lead to asphyxiation.

- To protect your lungs, wear a respirator, face mask, or use a damp cloth to cover your mouth.

- Use goggles to shield your eyes. Avoid using contact lenses.

- Protect your skin by wearing long sleeves and pants.

- Only drive during heavy ash fall if absolutely necessary, and reduce your speed significantly. Note that ash can clog engines, damage parts, and stall vehicles.

- If you cannot evacuate, stay indoors and keep doors, windows, and ventilation systems closed until the ash settles. Limit outdoor activity and remove outdoor clothing before going inside.

- Keep roofs clear of ash in excess of 4 inches.

- Avoid contaminated water.

- Take extra care of infants, the elderly, and individuals with respiratory conditions.

For more information about ashfall, visit the USGS Volcanic Ash website.

Volcano Preparedness Month

Each year, the DNR highlights volcano awareness and preparation throughout the month of May. However, for communities and individuals who live in volcano hazard zones, it's important to be prepared 365 days a year. Volcanoes don't play by the rules; preparation today, tomorrow, and every day is crucial to ensure safety in the event of an eruption.

We've provided you with a bounty of educational material and practical advice, but this blog is far from exhaustive. Here are some additional resources:

Washington State Department of Natural Resources: Volcanoes and Lahars

Seattle Office of Emergency Management: Volcanic Hazards

Webinar: What to Expect When You're Expecting a Volcanic Eruption

[1] National Geographic, https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/plate-tectonics-ring-fire/

[2] USGS, https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/vsc/file_mngr/file-103/

[3] USGS, https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/volc/types.html

[4] USGS, https://www.usgs.gov/programs/VHP/pyroclastic-flows-move-fast-and-destroy-everything-their-path

[5] Science Direct, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/rockfall

[6] USGS, https://www.usgs.gov/news/science-snippet/earthword-lahar

[7] Seattle, https://www.seattle.gov/emergency-management/hazards/volcano-hazards-including-lahars

[8] USGS, https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/1998/0519a/report.pdf

[9] DNR, https://www.dnr.wa.gov/programs-and-services/geology/geologic-hazards/volcanoes-and-lahars

[10] USGS, https://www.usgs.gov/programs/VHP/ashfall-most-widespread-and-frequent-volcanic-hazard