After a tornado ripped through Port Orchard, Washington in December 2018, the question on people’s minds was how common are tornadoes in the Pacific Northwest. We did some research and found some interesting stats.

The National Weather Service reports1 that Washington state averages 2.5 tornadoes per year, which ranks in the bottom ten states. Most are weak ones rated EF-1 or lower, like the one that occurred in Monroe in March of 2017. (We explain EF-1 and other tornado ratings below.) December tornadoes are rare in Washington; the few that do occur mostly hit in the spring, with fall a distant second.2

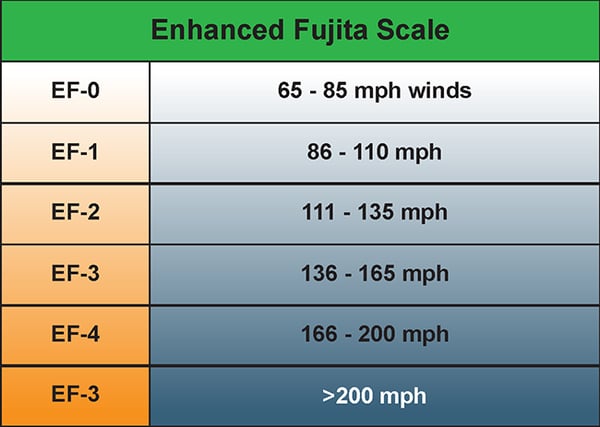

The Port Orchard tornado was an EF-2. The storm lasted approximately 5 minutes with wind speeds ranging from 120 to 130 miles per hour.3 The only other storm to hit the Puget Sound in December greater than an EF-2 was in 1969 near Kent and Des Moines, Washington.

There have been only about a dozen EF-2s in the state since 1954,4 most occurring in Eastern Washington. The worst year was in 1972, when an EF-3 storm killed six people and injured over 300 near Vancouver, Washington. On the same day, an EF-3 tornado struck in Lincoln County.

Tornado Ratings

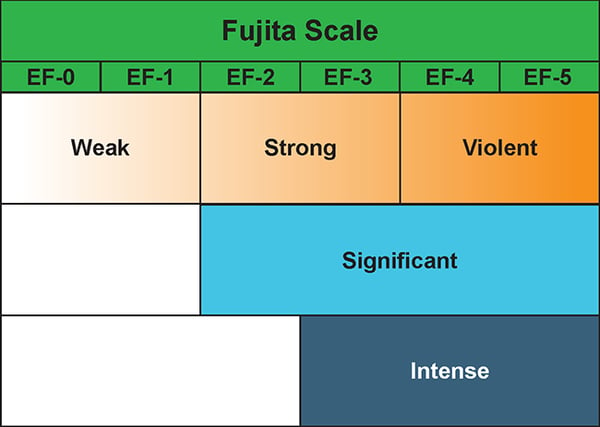

Tornadoes are rated by their intensity and damage to vegetation and property. There are two common rating scales, the Fujita scale (F-Scale) and the Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF-Scale). The Fujita scale is a tornado scale introduced in 1971 by Tetsuya Fujita and the scale evaluates total damage. In the United States the Fujita scale was replaced with the Enhanced Fujita scale, which is now the primary scale used the United Sites and Canada. The Enhanced Fujita scale not only considers damage but also takes into account wind speed.

Tornado Facts

Tornadoes are certainly not common in the Northwest, so there are many questions surrounding this natural phenomena.

Here are some interesting tornado facts:

- The average tornado has a wind speed less than 110 miles per hour, will be about 250 feet wide and only travel about two to three miles before dissipating.

- The average tornado only lasts about five minutes.

- In the U.S. there is an average of 1,200 tornadoes per year. Approximately 80% of those tornadoes are either F0/EF0 or F1/EF1, with less than 1% of them reaching a F4/EF4 or stronger.

- In the U.S., the month of May has historically been the most active month for tornadoes.

- Tornadoes have been observed on every continent with the exception of Antarctica, with the majority of them occurring in the U.S., especially in a region commonly referred to as tornado alley.

Tornado Myths

There are many myths about tornadoes. Let’s look at a few and bust them.

Myth: Tornadoes do not strike near rivers or large bodies of water.

Rivers, lakes and other bodies of water will not protect you from a tornado. Tornadoes can form over these bodies of water, and when they do they are called waterspouts.

Myth: Mountains protect you from a tornado.

Tornadoes have been reported on mountains as high as 12,000 feet, and a tornado can travel up a mountain for at least 3,000 feet. So, no, a mountain will not protect you from a tornado.

Myth: Tornadoes don’t form during the winter.

Obviously this is a myth since the Port Orchard tornado was in December. While unusual, tornadoes can occur in the winter. Tornadoes that occur between December and February tend to be more dangerous because they statistically move faster than those during the traditional tornado season. Tornadoes require two elements to form: instability and wind shear. Instability refers to warm and humid conditions in the lower atmosphere and cooler than typical conditions in the upper atmosphere. Wind shear is a combination of changing wind direction and increasing wind speed.

Myth: Tornadoes only cause damage when they touch down.

This myth is particularly dangerous because it means some people fail to seek cover. Violent winds and flying debris can be just as deadly as the actual tornado.

Myth: A stone or brick building will offer protection.

Maybe, but these types of structures may be hit with enough force to reduce them to a pile of rubble. The best thing to do is seek shelter in the lowest floor of a building, preferably under an I-beam or staircase, regardless of the type of building.

Tornadoes and Insurance

Washington residents do not have to deal with tornadoes on a regular basis, but the surprise tornado in Port Orchard raised questions about tornadoes and how homeowners insurance might cover the risk.

Our friends at the NW Insurance Council advise consumers to check with their agent regarding tornado and other windstorm coverage, which is typically part of a standard homeowner insurance policy in states like Washington.

Residents in parts of the country considered high risk for tornadoes or high wind damage may have limits on their wind coverage or higher deductibles. Coastal properties are most susceptible to damage from excess wind, and with $5.8 trillion worth of coastal homes at risk, proper coverage in those areas is critical.

High risk states like Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas have implemented a state-mandated risk-sharing program called a “wind pool.” These wind pools are run by government-chartered nonprofits to help insurance companies offer more affordable high-risk excess wind coverage not available through private insurance. Where wind storm exposure is unusually high, these pools are often the only catastrophic wind protection available to customers.

[1] MyNorthwest, http://mynorthwest.com/1220169/common-tornadoes-washington-state/

[2] MyNorthwest, http://mynorthwest.com/22133/spring-is-peak-season-for-washington-tornadoes/

[3] Q13 Fox, https://q13fox.com/2018/12/19/how-rare-are-tornadoes-in-washington-a-look-at-the-states-storm-history/

[4] Q13 Fox, https://q13fox.com/2018/12/19/how-rare-are-tornadoes-in-washington-a-look-at-the-states-storm-history/