About the Company

Who we are and how we serve insurers, agents, and Washington state residents.

CEO Perspective

Engaging thought leadership on key insurance industry issues from our CEO.

Meet the Team

Get to know the team behind WSRB’s trusted data and excellent customer service.

Careers

Learn about the benefits of working at WSRB and apply for open positions.

Underwriting Property

A guide to key risks in Washington state: fire and earthquakes.

Video Hub

Expert webinars, timely discussions, and in-depth conversations with industry leaders..

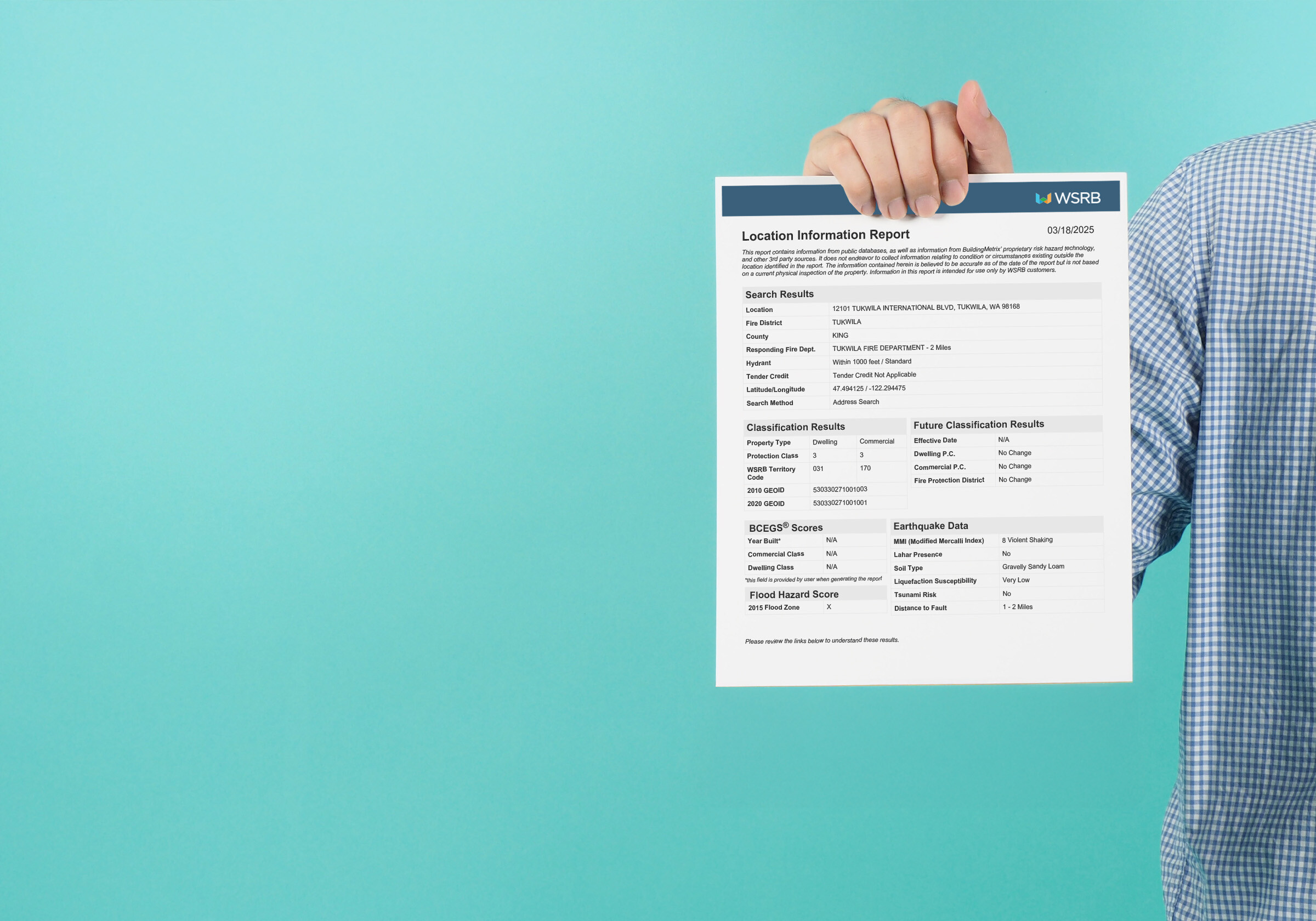

Commercial Property

Information on loss costs, policy rating, and assessment tools.

Industry Toolkit

Links to help you work smarter and serve your customers.

Protection Classes

The evaluation process explained from start to finish.

WSRB Blog

News on emerging risks as well as our latest products.

Library

In-depth content on essential insurance topics.

InsuranceEDGE

Weekly newsletter covering the P/C industry, curated by our experts.

About the Company

Who we are and how we serve insurers, agents, and Washington state residents.

CEO Perspective

Engaging thought leadership on key insurance industry issues from our CEO.

Meet the Team

Get to know the team behind WSRB’s trusted data and excellent customer service.

Careers

Learn about the benefits of working at WSRB and apply for open positions.

Underwriting Property

A guide to key risks in Washington state: fire, wildfire, and earthquakes.

Video Hub

Expert webinars, timely discussions, and in-depth conversations with industry leaders..

Commercial Property

Information on loss costs, policy rating, and assessment tools.

Industry Toolkit

Links to help you work smarter and serve your customers.

Protection Classes

The evaluation process explained from start to finish.

WSRB Blog

News on emerging risks as well as our latest products.

Library

In-depth content on essential insurance topics.

InsuranceEDGE

Weekly newsletter covering the P/C industry, curated by our experts.